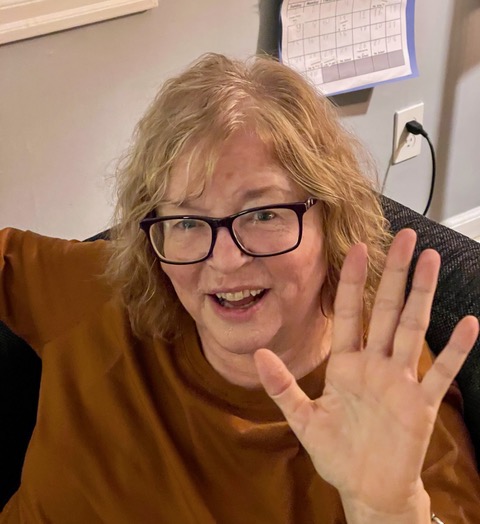

Remembering Lynn Robertson

With grief and sadness, we share the news that our friend and colleague, Lynn Robertson, passed away on Monday, October 4, 2021. She had enjoyed a wonderful weekend with her family in Portland, Oregon, and passed suddenly during the night.

We invite you to leave any remembrances here that can be shared with her family, friends, and colleagues. Lynn was a force of a nature and she will be greatly missed by all those whose lives were made better through knowing her.

(adapted from “Our Female Ph.D. Graduates at Berkeley”, celebrating 150 years of women at Berkeley.

https://psychology.berkeley.edu/psychology-part-ii-our-female-phd-gradua...)

Lynn Robertson received her Ph.D. in cognitive psychology from UC Berkeley in 1980, working with Stephen Palmer. She served as a research psychologist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Martinez, CA from 1982-1993 and on the faculty at the UC Davis School of Medicine, Departments of Neurology and Medicine (1984-1998), where she rose through the adjunct professor ranks. Lynn returned to UC Berkeley in 1998 as an adjunct professor in the Department of Psychology, Vision Sciences, and the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, while also a Senior Research Career Scientist in the Department of Veteran Affairs. She was last an Adjunct Professor Emerita at UC Berkeley.

Lynn's research in cognitive neuroscience has contributed significantly to our understanding of how the parietal lobes “bind” different features of incoming visual information to recognize objects and their importance. Think about a gray ball coming towards one’s head—one has to rapidly encode, using different regions of the cortex, the color, shape, size, and movement, to understand this is a ball and not a rock. Lynn's work helps us understand the brain regions and cognitive processes shaping this binding. She used neurocognitive measures in healthy persons and those with well-defined brain lesions to study these processes. Her work has major implications for understanding visual disorders in those with neurological injury and disease, including those with unilateral neglect, prosopagnosia (face blindness) and congenital visual-spatial deficits.

Dozens of her articles, including work published in Nature Reviews Neuroscience and in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences have been cited more than 100 times. She is the author or co-author of four books—including books describing cognitive neuroscience findings in synesthesia, spatial processing abilities, and (with Rich Ivry) hemispheric influences on perception—and over 200 research articles. She had garnered sustained research funding, mentored generations of students, shouldered numerous administrative and committee roles, including the advance of women in neuroscience, and had been named a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Association for Psychological Science, and the American Psychological Association.

Comments from Friends:

Lynn Robertson occupies a special place in my life as a cognitive psychologist. She was with me from the beginning of my career at Berkeley and our friendship and collegial association lasted until the end. There were years in between when we lost touch, but by the time she came back to Psychology at U.C. Berkeley, we connected again. We even jointly mentored a talented graduate student (Joe Brooks) whose dissertation beautifully joined some of our most enduring research interests: mine in visual figure/ground organization and hers in identifying the mechanisms underlying basic visual processes by measuring neural activity.

Lynn was one of my first (and favorite) graduate students in the Psychology Department at U.C. Berkeley. I was very lucky to have such a talented, energetic, and adventurous student so early in my career. She “cut her teeth” as a cognitive psychologist in my lab doing behavioral research on topics that came to define several of the fields to which she made some of her most important contributions: perceptual organization, reference frames, and hierarchical (global/local) processing. She came from the University of Nevada and was initially supported by a fellowship through the Institute of Human Learning (IHL), which was later rechristened as the Institute of Cognitive Studies (ICS) and later still as the current Institute of Cognitive and Brain Sciences (ICBS), name changes that, in a sense, echoed the trajectory of Lynn’s own research career.

Lynn was an integral, much valued, and well-liked member of the research lab I headed jointly with Eleanor Rosch back in the 1970s and 1980s. The students I recall from that era were a wonderful group. I remember with particular fondness the energetic debates over the relative merits of Gestalt vs. Gibson vs. Helmholtz. I especially recall Lynn arguing quite passionately with her friend Rutie Kimchi (see photo), who went on to distinguish herself, like Lynn, as an internationally renowned researcher on topics including perceptual organization, reference frames, and hierarchical processing.

But it was after leaving Berkeley’s Psychology Department with her Ph.D. that Lynn really began the career that defined her professional life: her contributions to the fast developing field of Cognitive Neuroscience (CNS). Lynn was one of the most interactive researchers I have ever worked with, and she jump-started her career in CNS through a series of collaborations that continued for decades. She started working at the Martinez VA Hospital and later at U.C. Davis, and finally back at U.C. Berkeley with many talented pioneers of Cognitive Neuroscience, including Bob Knight, Bob Rafal, Bill Jugust, Avishai Henik, Rich Ivry, Bob Efron, Marvin Lamb, Mirjam Eglin, Anne Treisman, Bill Prinzmetal, Shlomo Bentin, Michael Silver, and many others. Her research interests were broad in scope, encompassing a large sector of CNS, but focused primarily on neural mechanisms underlying front-end cognitive processes (such as perceptual organization, perceptual attention, visual search, and feature binding,) especially in patients with significant neuropsychological conditions (including alcoholism, unilateral neglect, schizophrenia, AIDS, agnosia, Balint’s syndrome, and synesthesia). This constellation of interests led her eventually and quite naturally toward work on rehabilitation that has been carried on by many of her students and collaborators. Her research and training grants were well supported by federal agencies (NIAAA, NIMH, and NSF) and she was appointed as a lifetime career scientist in the Veterans Administration.

In addition to well over one hundred publications in refereed journals, she published four significant books. First, together with Terry Knapp she edited Approaches to Cognition: Contrasts and Controversies (1986, Erlbaum; reprinted in 2017 by Routledge) where a variety of authors weighed in on the strengths and weaknesses of many different theoretical and methodological approaches to understanding cognition that were in play at the time. It is a fascinating snapshot of views from an era (mid-1980s) when CNS was just getting started and competing with other more established perspectives for “a place at the table.” Needless to say, it succeeded rather spectacularly, and Lynn was in on the ground floor.

Together with Rich Ivry, she co-authored The two sides of perception (1998, MIT Press), a deep dive into the nature and implications of hemispheric lateralization in perception and cognition. Their novel perspective was that left and right hemispheres differ in their abilities to process frequency information – spatial and temporal frequencies in vision and auditory frequencies in hearing. In particular, their double filtering by frequency (DFF) theory proposes that the right hemisphere is more proficient at processing low frequencies and the left hemisphere more proficient at high frequencies, where “low” and “high” are defined not absolutely, but relative to the frequency range in which a given task must be accomplished.

In 2004 Lynn collaborated with her former graduate student, Noam Sagiv, to edit an excellent collection of essays titled Synesthesia: Perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. The genesis of this collection was a Cognitive Neuroscience Society symposium held in San Francisco in 2003 when empirical research on cross-modal sensory experiences was just taking off. With chapters by many of the pioneers of this fascinating phenomenon, it provides early insights into how and why a relatively few individuals automatically, for example, see colors while hearing sounds and feel textures while tasting flavors. Among the most intriguing topics is how such completely subjective experiences can be studied using rigorous, scientific methods.

And most recently, Lynn published Space, Objects, Minds and Brains: Essays in Cognitive Psychology (2012, Psychology Press), which presents her perspective on many of the topics on which she made some of her most important and enduring contributions: spatial reference frames, attention, object formation, visual awareness, and feature binding. The book combines insights from her own research together with findings from others to explore the cognitive and neural basis of spatial representations. It is an impressive sample of her signature style of research, well-grounded in both behavioral psychology and neuropsychology yet striving to integrate them rigorously with an eye toward understanding and rehabilitating some of the clinical conditions that so firmly grounded her science.

In her more than 40-year of scientific career, Lynn Robertson produced a substantial body of high quality research in cognitive neuroscience before her passing earlier this month. But there is a real sense in which it was her direction of her laboratory that is her most enduring legacy. The number and quality of research assistants, graduate students, post-docs, and faculty who collaborated with Lynn at UC Berkeley and UC Davis in producing and publishing new results is impressive indeed. The set of her graduate students at UC Davis and UC Berkeley include Marcia Grabowecky, Krista Schendel, Noam Sagiv, Mike Esterman, Alex List, Joe Brooks, Ani Flevaris, Matthew Baggott, Ayelet Landau, Francesca Fortenbaugh, Ali (Yamanashi) Leib, Bryan Alvarez, and Allison (Connell) Pensky. Her post docs include Cameron Carter, Min-Shik Kim, and Tom Van Vleet. And a partial list of her faculty collaborators are named above.

We will all miss her very much.

-- Steve Palmer

My own memories with Lynn go quite far back, too. She gave a job talk at Oregon, probably in my 4th year of grad school, a time when I was just beginning to work with neurological patients. I remember my advisor, Steve Keele bouncing off the walls with excitement after the talk, only to be very disappointed the next week to hear she had come up short. While I was sorry she didn’t join us in Oregon, a few years later I was thrilled to hear she was part of the Martinez Neuropsych. So instead of getting Lynn as a graduate school professor, I got her as a lifelong colleague and friend.

Soon after arriving, Lynn became my chauffeur of sorts, picking me up en route to Martinez for neurology rounds. Great opportunity to brainstorm about mutimodal hemispheric asymmetries, a discussion that culminated five year later in our book, The Two Sides of Perception. We stuck to our initial pledge to spend every royalty check dining at Chez Panisse. Brent, Lynn’s husband who demanded his night on the town even when the royalty checks had dwindled to single digits.

Lynn was passionate about her science and the life science afforded. Her excitement over the latest results from her collaboration with Anne Treisman were only matched by her excitement over recent or upcoming globe-trotting adventures with Anne and Danny Kahneman. I was sorry for our cogneuro community when she retired a few years ago but Lynn was eager to shed work responsibilities so she could enjoy long visits in Oregon with her nephew Travis and his ever-growing family.

We will miss her.

-- Rich Ivry

Lynn was my post-doc advisor from 1996-1999 at UC Davis and the VA in Martinez. My dissertation at Michigan was on the intersection of attention and working memory, so working with her was a dream come true. She strengthened my love for neuropsychology and exposed me to patients with rare conditions like Balint’s Syndrome and prosopagnosia – experiences that I continue to share with students and mentees today. She was very giving of her time, always excited about her research questions, and very supportive of my growth as a cognitive neuropsychologist. Although I haven't spoken to her in many years, I am very sad to know that she is no longer with us. I am truly grateful that I had the opportunity to learn from her. She will definitely be missed. My sincerest condolences to all of her family, friends, and colleagues.

-- Lisa L. Barnes

I knew of Lynn's work since I was an undergraduate working in Rich Ivry's lab, having read the two sides of perception, thereby contributing to one of their Chez Panisse dinners :) But I got to know her better in 2000 when I was doing my postdoc with Mark D'Esposito. I was on the job market preparing to give a job talk. Lynn offered for me to do a dry run on her lab. I did, and it was ok, but not very good. So I revised and practiced, and she listened to the whole thing again. Then, I revised and she gave me more feedback. With Lynn's help, my job talk was a big success. She even anticipated the question Ken Britten was going to ask, so when he asked it, I handled that with ease. It is crazy how much time she was willing to spend to help me out, for no other reason than that she was just really kind. I always was happy to see her any chance I got, but in the last few years, I just never had a good opportunity and wish that I could have talked to her one more time.

The world of academic science can be brutal but it can also be fun and wonderful. Lynn was one of those special people who created those joyful moments, and made our world a better place. It's now on the rest of us to try to do what we can to pay it forward.

-- Charan Ranganath

Lynn Robertson was an enormous influence on my research career and a role model for female cognitive neuroscientists. I first worked with Lynn during a research rotation during my first year of graduate school at UC Davis, but the work I started during that rotation continued for several years, including future collaborative work when I came to NIMH as a post-doctoral fellow. Lynn was not my official grad school advisor, but she had a significant impact on my career. As a first-year graduate student, Lynn generously brought me to Anne Treisman’s lab to observe a patient with bilateral posterior parietal lesions and encouraged me to join in exploring patient R.M.’s behavioral deficits. The Berkeley lab was a beehive of activity, with testing occurring in multiple small rooms off the central suite. But the best part was the crowded main room where a large mix of grad students, post-docs, and professors excitedly discussed ongoing work and speculated on what it meant. Lynn made even the beginning students feel welcome to contribute. (And she didn’t even blink when one of us had the gumption to suggest that we should submit our manuscript to Science.)

Lynn’s brilliance as a scientist was the realization that adapting cognitive psychology tasks to probe the deficits of patients with focal neural lesions could provide a way to map the function of different brain regions. Together with her colleagues at Martinez (Bob Knight, Bob Rafal, and others), Lynn’s research provided important insights into the functional organization of the human brain, preceding the development of task fMRI. This was at a time where brain lesions were confirmed by low-resolution CT and identifying overlapping regions of interest involved physically tracing CTs from multiple patients. Behavioral neurologists were way ahead of other fields of neuroscience—Psychiatrists did not start to think about what they could learn by utilizing parametric testing with cognitive neuroscience tasks until 1-2 decades later. At one point during my post-doc in the intramural program at NIMH, I complained to Lynn that not having an MD seemed to be a liability. Her response was: “Oh, but they need you. Who else is going to design the tasks they use to test their hypotheses?”

Lynn also shared some of the politics of academia with her mentees. For example, there were competing theories about whether it was kosher to use an overlap approach for localization of neural correlates or whether only single patient studies were valid. When this theoretical debate began to affect her journal and grant submissions, Lynn used this to educate us to the realities of scientific competition. She was also the only mentor I ever had who let us know that there were multiple ways to have a productive scientific career; tenure-track positions were not the only route. I think she was trying to steel us for the real world and I appreciate how open she was to sharing her experiences.

Aside from being a creative scientist and good mentor, Lynn was a genuinely nice person who was generous with her time and attention. She had a way of making it seem like we had all the time in the world to engage in scientific discussion and plan a set of hypothetical experiments. This in turn gave us the confidence to explore new areas and approaches on our own.

-- Stacia Friedman-Hill

Lynn was my advisor during the end of my doctoral studies at Berkeley. She was all the things to me that so many have already written -- ultra smart, caring, rigorous, supportive, and challenging in all the right ways. I am thankful that I took the time earlier this year to reconnect with Lynn. Though it was only via email, I got to tell her some of the ways that she positively impacted my life just by being herself while I was at Berkeley. I shared with her that it was so meaningful to me to have a strong, incredibly brilliant, kind, and not a little intimidating woman to look up to all of those years. That I often speak with students who are applying to grad school and anticipating the interview process about the story of my interviewing at Berkeley. The only interview that really threw me for a loop was when I talked with Lynn! I remember talking with one of her current grad students on the BART back to San Francisco about it afterward and she assured me that, paraphrasing, "Lynn is just a bad-ass." Thinking back on it now, I hadn't had much opportunity to interact with a female academic until that moment. Having her guidance as I set out on my professional journey was incredibly meaningful and I am so thankful. I try to emulate many of Lynn's traits in how I mentor my own students now as a faculty, and I know my students are the better for it. I was shocked to hear the news about Lynn's passing. My one comfort is that she was visiting family who she had told me many times were the light of her life, especially her retirement. I'm thankful that Lynn had a few years of retirement to just revel in life, in her own words, "Reading all day in my jammies, looking at the view from my sunroom and conversing with my neighbors across decks has given a new perspective on life. It’s pretty special." I'll miss you Lynn.

-- Allison Connell Pensky, Ph.D., class of 2013

Hi everyone, what a sad context to remember Lynn and all of you in. I have so many fond memories of Lynn from graduate school. Lynn, together with Bob Rafal, were my academic parents. Without her, I would not be where I am today. Lynn taught me how to do research, was a great mentor, and a friend. Though I have strayed far from work with neurological patients, she gave me the scientific tools and belief that I could excel and do any type of research. Lynn was always very warm to me (Even though I ended up working with Bob:)). I fondly remember my last meeting with her a couple of year back. We were having lunch in Berkeley after being out of touch for many years, and it was like no time had passed since we had our meetings, years back, at the Cognitive Neuroscience at UC Davis. She was full of warmth, empathy and great ideas about research. Exactly like a great parent would be. I already miss her a lot.

-- Shai Danziger

It was 1993 when I asked Lynn if I could do a 1 quarter rotation in her lab at the UC Davis Ctr for Neuroscience. Four years later I was still sitting in Lynn’s lab having earned a PhD under her guidance. Getting my PhD was a balancing act as I had 3 children at home, but Lynn always gave me the support and flexibility to make it work. I will always be grateful to her for that.

Lynn always taught her graduate students to be “hands on ethical researchers”; never straying too far from the data itself or the subjects who generously gave their time to our research. I remember in the very beginning Lynn wanted to be sure that I knew how to program a cognitive experiment from beginning to end. I sat for many many hours in Lynn’s windowless testing room struggling as I learned how to program a Stroop experiment using the DOS based MEL program. Although I chuckle now, at the time it was a bit tortuous.

After I graduated and took on a faculty position in Psychiatry at UCDMC, Lynn was my role model for how to survive on soft money. I would often call her for career advice and she was always available to share her wisdom. She was the best mentor one could ask for. In more recent years, Lynn and I would meet once or twice a year at our favorite Berkeley 4th St restaurant. Just before the pandemic hit Krista Parker and I were so lucky to have had lunch with Lynn. As the 3 of us said our good-byes, we all hugged and shared how much we meant to each other. I will treasure that memory. I will miss you, Lynn.

-- Ruth Salo

Lynn Robertson was an undergraduate at University of Nevada and a research assistant in my laboratory. She functioned at the level of our graduate students; treated as their equal by both faculty and fellow students. I did not think continuing at UNR for graduate training was in her best interest, so I advised her to move on. Having friends and colleagues at UC Berkeley (most notably Postman and Keppel), I strongly recommended her. After all these years it is nice to know this was the right thing to have done. I remember favorite faculty from my student days, and sadly now with Lynn’s passing, fond memories of a favorite student are added.

-- William P. Wallace

Lynn and her husband Brent were my next door neighbors from 1987 on. They were the best neighbors I ever had. But Lynn was far more than a next door neighbor; she was family. Confidante. Drinking buddy. One of the few people I counted as a best friend. We could -- and did -- discuss anything, often at all hours. And the dogs! As a dog lover, Lynn was unsurpassed; whether her own dogs or her numerous canine guests, their spirits and Lynn's always soared together. Losing her is an awful blow, not the sort of thing one "gets over." Yet although I am in a profound state of grief, I know that Lynn would not want me or any of her friends and family to let grieving become the enemy of living. Lynn, we miss you!

-- Eric Scheie

Lynn,

Here, there, anywhere

Local, global, everywhere

You have changed and inspired us.

Thank you!

-- Kia Nobre

In almost all my memories of Lynn she is smiling, and often I can hear her distinctive laugh and the warmth of her voice. Lynn was a friend to me, but she was perhaps most important in my life because she was Anne Treisman’s best friend. The period in which they collaborated on the study of their very special Balint patient was a particularly happy chapter in Anne’s life. They enjoyed the shared experience of lugging heavy computers (yes, they were heavy then) to visit the patient at home, and the delight of discussing hot-off-the-plate results and future experiments with a friend she loved and trusted. Anne could be shy and reserved, but in Lynn’s company she opened up and blossomed – she always returned happy from their joint explorations. The experience of camaraderie was precious to her, and she cherished Lynn for the rest of her life.

We shared several wonderful vacations with Lynn and her husband Brent, on French canals and on an Antarctica cruise. On those occasions Lynn was both the source and the object of much good-hearted banter, especially in her exchanges with Erv Hafter, often addressing her choices of expensive wines for our collective consumption. In those happy years Lynn was always the life of the party. That is how I will remember her.

-- Daniel Kahneman

Lynn was my PhD advisor, and she had a profound influence in me both as a scientist and as a person. Her way of leading allowed us complete autonomy over our work- and yet her innovative and critical thinking were always visible to influence our perspectives. She was a brilliant woman, and an incredible example for me of a strong and successful woman leader. She was also a caring mentor. She invested in all of her students, and tailored her mentorship to our individual needs. I will never forget how much time she invested in helping me to become more comfortable speaking - and defending my work- in a public (and sometimes adversarial) setting. The skills she taught me I’ve carried with me in all areas of my life, and still hear her voice when preparing for a big presentation. Above all, Lynn was full of joy. When I think of her, the first thing that comes to my mind is her laughter- she was always laughing, enjoying her life- and bringing all of her students into that joy. I miss her greatly.

-- Ani Flevaris

Lynn was a wonderful colleague—inspiring, imaginative, thoughtful, helpful, and kind! As others have noted, she always had a lovely smile on her face—captured in the historic 2013 picture of our female faculty gathered for a Women's Faculty Forum meeting. Although we worked in different areas, I well knew what a tremendous contribution Lynn made to the department and to her field. She leaves a great void here and will be missed.

-- Rhona Weinstein

It’s so hard to write about Lynn. Her loss feels like my heart has been ripped out. So much was lost – by all of us – and so much remains in memories she gave us. I’ll just mention three things she taught me from the example of how she led her life.

By her example, she taught, in so many ways what it was to live a courageous life. Growing up in the “Biggest Little City,” she braved graduate school at Berkeley. Graduate school is never easy, but with her characteristic pluck she became in the words of Steve Palmer “among my best and most successful, graduate students.”

And then she took two more brave steps. She created a path as an independent scientist doing basic research at the Veterans Administration. This eventually led to her lifetime appointment as a Research Scientist. Second, she was one of the founders of a new field, cognitive neuroscience.

She showed me how to live a courageous life in a dozen other ways. I will never forget her bravery in Brent’s final years.

Second, Lynn knew how to live life to the fullest. There were gourmet meals, fine wines, and wonderful trips with Brent and her other good friends the Hafter’s, Danny and Anne, Nina and others. When I had the privilege of being part of her lab at Berkeley, I don’t think there was a birthday uncelebrated or a missed occasion to open a bottle of champagne – at lab meetings. I will never forget the lab parties she hosted at her house to celebrate so many happy occasions. By her example, she taught us how to live.

Finally, Lynn showed me the power of empathetic friendship. I believe that those of us who are fortunate enough to be in science are blessed. We get to look for -- and occasionally find -- the sweet honey of understanding. But in any search in the beehive, we occasionally get stung by rejection from a journal, grant, advancement, job, whatever. I had just received one of those stings; it was a bad as I have experienced. I happen to see Lynn walking down Shattuck Ave. I hadn’t seen her for a while so we stopped to chat and I started to tell her my tale. I didn’t get the first sentence out of my mouth and she did what did your true friend would do. She gave me a hug.

Lynn showed us what it meant to live a courageous life. She showed us how to live that life with gusto. And she was my friend.

-- Bill Prinzmetal

Lynn was one of the earliest and most impactful mentors I've had in my (now several) careers. She paved the way for me and so many others in ways I'm sure I don't even realize yet. She was undoubtedly an intellectual force with a long and impressive career. What I think made her even more impactful was that she did all of that while also bringing a rich tapestry of people together, binding us if you will. I have a great many things to thank Lynn for, and I hope she heard my gratitude in life. I'm sure I will go on missing her and also celebrating the indelible impact she made on my life.

-- Alice Albrecht

Lynn was a very close and very dear friend of mine. We were both graduate students in Berkeley. In the early years of my graduate school I lost both my parents a year apart. I was devastated. I will never forget how Lynn and Brent embraced me with love and tender. We became the best of friends. Later on Dan Morrow (my boyfriend then) joined us, and the four of us spent a lot of time together, enjoying lovely dinners and beautiful trips. Lynn and I also had common interests in cognitive psychology, and we had conversations, including sometimes argumentation, about issues in perception and cognition. When I left back to Israel, it wasn’t easy to keep the close friendship with the geographic distance, especially for Lynn. Nonetheless, we kept track of each other life. Lynn has always had a special place in my heart. I loved her and appreciated her friendship, her joy of life, her cleverness, and her devotion to her husband Brent. I’m flooded with fond memories. I miss her.

-- Rutie Kimchi

Lynn introduced me to the emerging field of cognitive neuroscience during my psychiatry residency training at the VA in Martinez. I had no background in cognitive psychology and she was incredibly patient with me, giving me papers to read and helping me to try to think like a cognitive experimentalist. There was very little work in psychiatric disorders at that time but for me that initial exposure was an epiphany, this was the basic science we have been waiting for to begin to understand the mechanisms of human mental disorders. Lynn was supportive and also highly skeptical and rigorous. She was also very curious and creative and saw possibilities for the field that were hard to imagine. She helped me design studies in anxiety and eventually in schizophrenia, which became my main area of work. After we published our initial studies I moved to Pittsburgh and got involved with the modelers and neuroimagers there, but Lynn always stayed in touch and we talked at SFN and CNS. Just a few years ago we found ourselves both giving keynotes at the Australasian Cognitive Neuroscience Society meeting at Monash University. It was fun seeing the origins of my own work in her approach and very nice to catch up with her, though her husbands illness was weighing heavily on her mind. She got a lot of joy from her friends and family at that time and I have heard that these past few years have been good for her. It is hard to imagine that she is gone.

-- Cameron Carter

Lynn was radiant. When she spoke about the brain, her eyes shone and the room lit up: yes, we are on our way to understanding the most mysterious object in the universe. She saw the brain up close in patients with various types of neurological damage, and brought us a unique grounded understanding of its function. When I joined Lynn’s lab as a research assistant, what struck me was how she approached research with both playfulness and intellectual depth. My experiences in her lab led me to a career in cognitive neuroscience and she was there for me all the way through. Lynn was radiant also outside the lab. I remember running into her and her husband at Cesar’s one time. They were talking and laughing, so happy, and I remarked how beautiful that moment was. I miss the light that Lynn brought into this world.

-- Tatiana Aloi Emmanouil

When I moved to Berkeley in 1999 to join Steve Palmer's lab to work on perceptual organisation, Lynn generously welcomed me into her Cognitive Neuropsychology lab and served as my second supervisor because I also had strong interests in neuropsychology. I can't express enough how much working with Lynn enriched my PhD experience through exposing me to neuropsycholical patients, learning EEG methods, connecting me with important people in the field, and most importantly, inspiring me with her own enthusiasm for science. Lynn also made sure that I had a funded role in her lab for much of my time at Berkeley. I am indebted to her for the opportunities that she gave me and which continue to shape my career now. Outside of the lab, I have many fond memories of parties at Lynn's house in the Berkeley hills. Lynn always had a smile on her face and knew how to throw a party! I was lucky enough to catch up with her over dinner when I was visiting Berkeley a few years ago. Although I'm sad that we no longer have her with us, we must continue to cherish all the positive things that she created in science and in our lives.

-- Joseph Brooks

Lynn Robertson was a force in the field of cognitive neuroscience and she was also an amazing mentor and role model for women in science. Lynn had a keen sense for experimental design, particularly in regard to working with brain injured patients. I will never forget how she encouraged us to use our own experiences to provide insights into a patient’s deficits, while at the same time cautioning us as to how limited and constrained our own experience might be in comparison to that of a person who had experienced a brain injury. Lynn was also a gracious and wise friend who offered excellent advice as I struggled to balance motherhood and career. I feel very lucky to have worked with and been mentored by Lynn. No one’s eyes sparkled as much as Lynn’s during a good debate or discussion of a dataset. Lynn’s passion for science was palpable, infectious, and inspiring. I will dearly miss Lynn’s wisdom, her passion for science, and most of all - her uncanny ability to see “the bigger picture”. It was always Lynn who helped me see the forest from the trees!

--Krista Schendel

I met Lynn while completing my clinical internship at the Martinez VA. She attended a grand rounds where I was sharing my research and we immediately hit it off given our shared interests in attention and the ‘neurological neglect syndrome’. Lynn was uniquely unencumbered by her academic success and often presented as an enthusiastic ‘student of research’. She invited me to join her lab as a post doctoral research fellow and I was ushered into the world of Cognitive Neuroscience. After spending my graduate school training 'hanging out' with rats, I was thrilled to begin the work of translating basic science to clinical therapy. Lynn was truly innovative in this regard, as one of the few scientists at the time that had bridged the gap between cognitive theories and neuroscience. Moreover, Lynn was a sweet soul, a supportive mentor and a generous friend. I’m very grateful for our time together and will miss her generous smile and infectious laughter.

-- Tom Van Vleet

I found my way to Lynn because her nose was running. I was in my last semester in college as a cognitive science major, sitting in Rich Ivry’s class, having decided to ditch my post-graduation plans to go to Argentina, and instead pursue cognitive neuroscience. Lynn was guest lecturing about reference frames (“arrow man” specifically) and I was transfixed by the elegant scientific study design. Then, Lynn’s nose started running and she asked the large audience of undergrads if someone had a tissue. Total silence. “Surely … someone has a tissue.” One manifested, and she rolled on with her impressive talk after blowing her nose. Just like that. Together, her scientific elegance, her confidence and her authenticity just hit me—I was in absolute awe. (I remember later comparing her to watching Kim Gordon perform on stage.)

Shortly thereafter, I interviewed with Lynn at the VA in Martinez, and started working as her lab manager. I was there for the transition from slide carousels to power points, from writing and editing papers in VI to Office, moving labs from UC Davis to UC Berkeley (including glorious decisions for paint and carpeting). But, I also learned to work with individuals who had had strokes, read hospital charts, process IRB protocols and grants, witness the editorial process, program studies, troubleshoot equipment problems, collect and analyze data. And I got the research bug. After two years, I started as one of Lynn’s graduate students, where I stayed for the next six-plus years. In those eight years, Lynn trained me on all things boring and glorious in our science. She explained political tensions diplomatically but truthfully. She talked through hard personal topics openly. She was extremely generous with me. She trusted me to watch her house and her dogs, Pita and Pandora. She also hated telling me when the dogs died because she knew I would take it hard. Lynn got me. She saw my flaws, my strengths. She got irritated with me, but more often, got excited for me, personally and scientifically. Most of all, I deeply appreciate the authenticity she always showed me.

Whenever I think of Lynn, I can hear her saying “Oh, Alex!” I can see her big smile, her proud, practically-superheroic posture, her hair shimmy, and I hear her laugh. Here we are, happily reunited in Berkeley in March 2019, some 20+ years after that life-altering runny nose incident.

-- Alexandra (“Alex”) List